Ever since the dawn of civilization, Egyptians farmers have played a major role as pioneers in irrigation methodology and technology. Accumulating wisdom and knowlege to be passed down and built upon generation after generation for thousands of years.

They developed a wide variety of sophisticated strategies which enabled them to effectivly harness the power of the Niles water; amplifying its fertility to such a magnitude that they were able to baffle modern scoentist with their impressive feats of strength and engineering. Leaving behind monumental landmarks, famous across the world over.

If it werent for these innovative irrigation developments made by ancient farmers of the nile delta and fayoum oasis,, all of the other landmark acheivements of the Egyptian civilization most likely would have never been possible. So addressing this subject should be important for anyone interested in discovering how the Egyptians accomplished what they did(NOT ALIENS!!!)

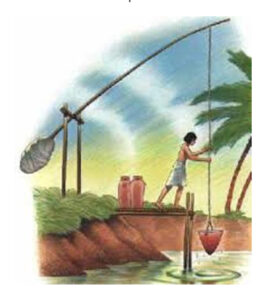

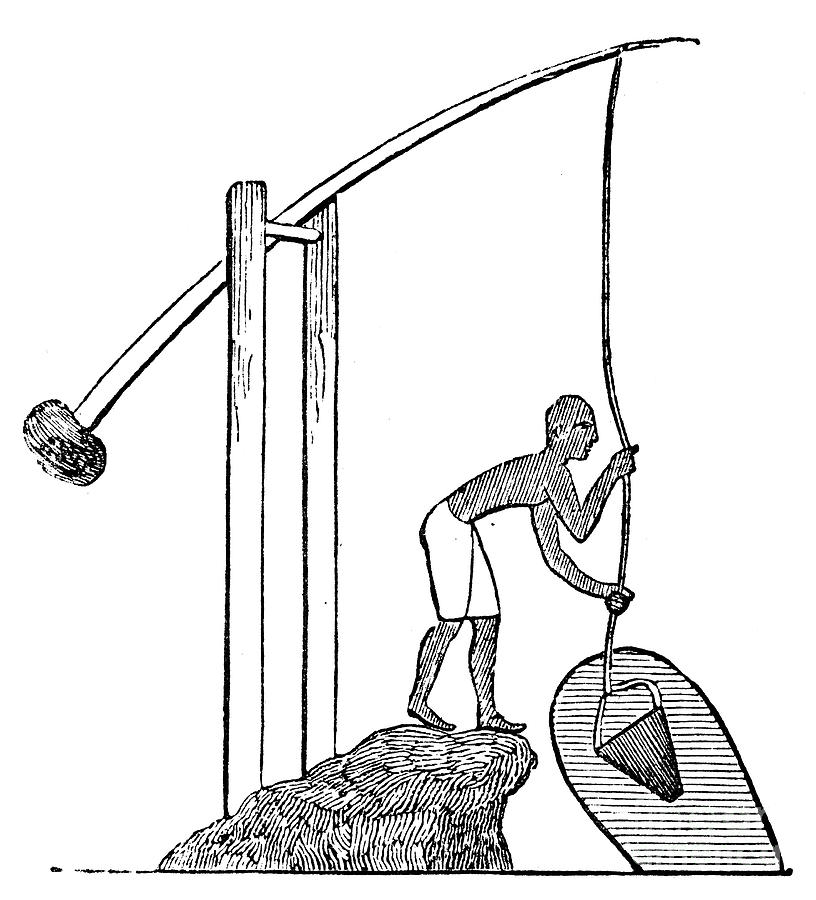

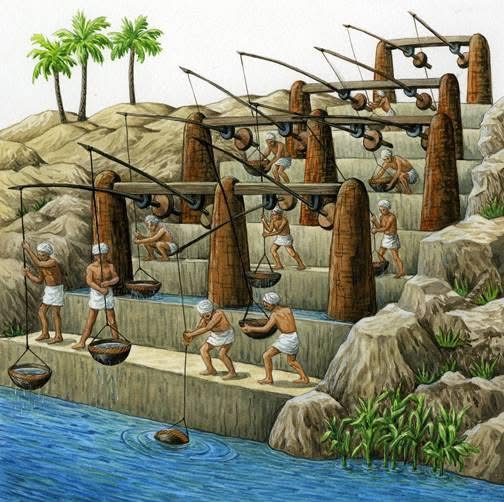

The Shadoof:

Starting with the most ubiquitous and well established ancient irrigation devices depicted in ancient egyptian archeological sites: the Shadoof.

The shadoofis was typically constructed on a sturdy vertical frame, supporting a long pole or branch, with the fulcrum positioned about one-fifth of the way from the short end.

On the longer side of the pole hangs a water‐holding vessel—such as a bucket, leather skin bag, or bitumen-lined reed basket—often fitted with a detachable bottom that allows water to flow out immediately.

The shorter side of the shadoof carries a counterweight (clay, stone, or similar material) which balances the system: when properly adjusted, the weight will hold a half-filled vessel aloft, so lowering an empty bucket down into the water requires a certain amount of downward pressure.

By rocking the pole in a see-saw motion, the operator submerges the vessel, fills it, then swings it upward and pours its contents into furrows that channel the water from its source(typically a river or pond)—into a wider network of irrigation ditches.

In some cases, farmers would even use multiple shadoofs to transfer water from a river or canal to a higher elevation. This would involve a series of shadoofs set up along a slope, with each shadoof lifting in cooperation

Due to the significant amount of effort required, ancient farmers would carefully time their use of water to ensure that they didn’t overuse or waste water. They would often irrigate their crops during the cooler parts of the day, such as early morning or late afternoon, or order to reduce evaporation.

This new-found irrigation ability offered by the shadoof allowed farmers to cultivate crops year-round, contributing to increased food production and a growing population.

The shadoof also enabled the cultivation of crops in new areas, expanding the range of crops available and increasing the variety of food options.

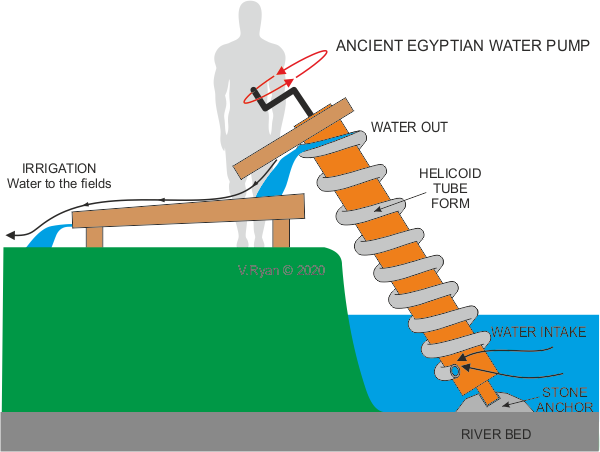

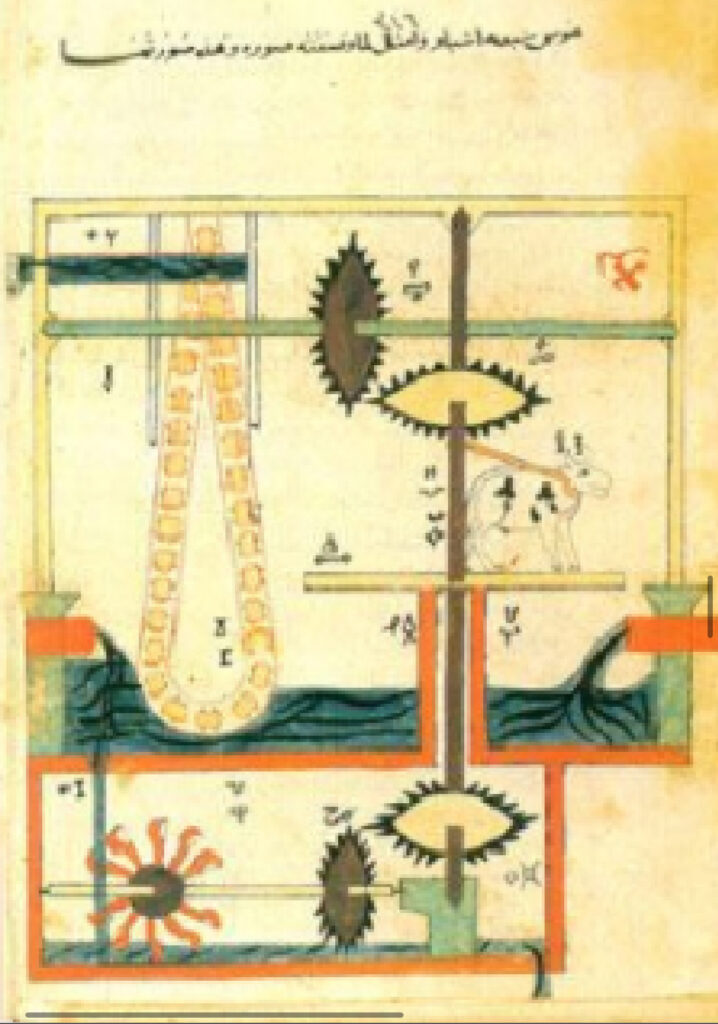

The Tambour(screw-pump)

The ancient tambour, often called the Archimedean screw, is one of earliest hydraulic machines and the first ever water pump created by man.

Though later named after the Greek engineer Archimedes, archaeological and textual evidence suggests that it was actually developed long before his time; in ancient Egypt, not Greece.

Archaeological and textual evidence shows that farmers in Ptolemaic Egypt were already using simple helical-tube pumps to lift Nile water for irrigation far before Archimedes ever described the device.

these early versions consisted of a spiral tube wound around a central shaft housed in a half-cylinder; as the assembly was turned by hand (or later by animals), water climbed up the spiral into elevated channels

For smaller water-screws (diameter ~20-30 cm), one person could crank the handle continuously. Although larger installations(perhaps 50-60 cm across) often employed a donkey or two men walking in a circle, turning the shaft via ropes and pulleys.

While Archimedes of Syracuse never claimed to have invented the screw, he fid provide the first surviving detailed account of its mechanics around 234 BC, during or shortly after his visit to Egypt.

Regsrding its physics, the lower mouth of the screw sat partially submerged in the river, canal, or water pit. Farmers sometimes built small landing platforms or decks to steady the device. Steeper angles raised water higher but required more turns per liter; shallower angles delivered volume more quickly but to a lower height.

The tambour often worked alongside water-storage systems-reservoirs, cisterns, and qanat-style tunnel networks-so that lifted water could be held, measured, and released according to crop needs.

A small team operating a screw pump could irrigate as much as ten times the acreage that a pair of laborers could with shadufs in the same timeframe.

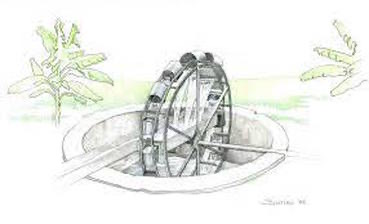

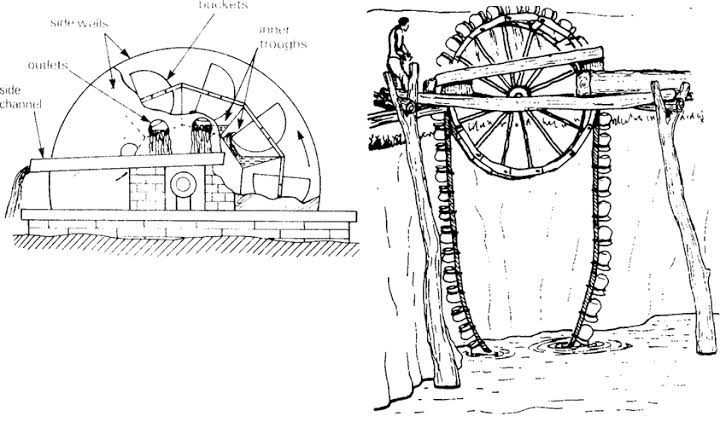

Sakkia (“irrigation wheel”)

Archeological evidence suggests that the sakia may have been used as far back as the Old Kingdom, during the time period when the Great Pyramids were being built.

The earliest known depiction of a sakia can be found on a wall relief in the tomb of Djehutihotep, who served as the governor of the city of Deir el-Bersha during the Middle Kingdom period (2055–1650 BC). The relief shows a group of men turning a large sakia to lift water from the Nile river for irrigation.

Mechanically, the sakias was comprised of 2 primary Axels:

The vertical axel (bucket wheel): in which buckets or clay pots were affixed around its rim or to a continuous belt, forming pockets that trapped water.

The Horizontal drive axel: Turned by oxen, donkeys, or human operators, this wheel transmitted rotation via a shaft to the vertical element.

As the vertical wheel rotated slowly (2-4 rpm under animal power), each bucket scooped water from the source-river, canal, or well-and carried it upward, discharging at the top into a trough. Wheels ranged from 2 m to over 4 m in diameter, allowing lifts of 10-20 m-far exceeding the 3 m limit of a shaduf

By elevating water above the floodplain, the possession of a saqiya enabled farmers to cultivate on higher terraces and plateaus, expanding arable land beyond the reach of annual inundation.

Farmers could maintain perennial gardens of date palms, vegetables, or flax on marginal soils. Even in areas where surface water was distant or unreliable, sakias where used lift groundwater from well’s that were previously unproductive.

Damns

The damn is the most basic and earliest known irrigation strategy implemented by man.

These structures have been used to manipulate waterways for irrigation purposes since the very begining of agriculture. Possibly because it just comes along with basic common sense and logic. “We need more water ‘here’, so block the flow ‘there’” Very simply yet effective method of hydrating fields surrounding a waterway.

Although, over time, the uitilzation of these damns was augumented and improved to become more and more complex and efficient. To encompass various methodologies for use in different situations. Such as reserving and retaining water during high flow, to trap it and keep it reserved it for later use during lower flow periods. They used this extra control and precision in their irrigations methods; to time their water application for better hydration outside of the natural rythms of the river.

They eventally learned to keep track of the annual patterns of water flow and to preemptively predict flooding or drought and they used these damns and resevoirs to protect themselves against these natural phenomenon. Over time they gained tremenedous experience and eventualt became experts at formulating strategies to harness the flow through their use off dams, dikes, canals, reservoirs, ect.

They would build mini damns and mini dikes to control and concentrate water flow to specific areas of their field which needed it most.

Ancient farmers would often rotate their crops to make the most efficient use of the available water. For example, they might plant crops that required less water during a dry season, or they might switch to crops that were better suited to wetter conditions during a rainy season.

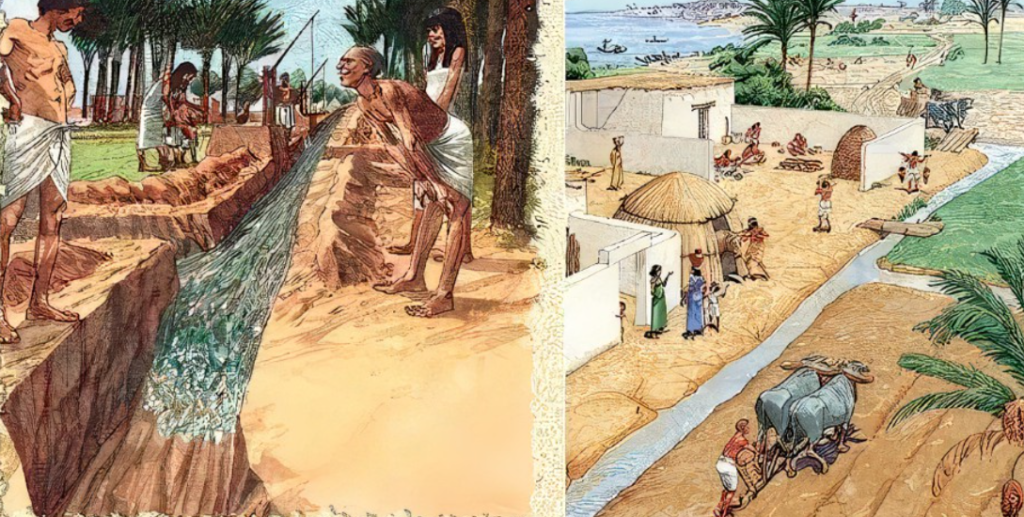

Canals

Naturally, alongside the emmergence of the earliest irrigation damns came the development of irrigation canals as well.

Because once you block the water and have it trapped, you are going to want to redirect it and divert it for further use in the irrigation of addition farmlands.

So the ancient egtyptian naturally developed man-made waterways, like new blood vessels(formed with hard physical labor). All for the sake of delivering additional nutrition and hydration to the surrounding croplands. To expand the lifeblood of the nile river further and further. For the sole purpose of spreading life and vitality.

These waterways were excavated through the use of shovels, hoes, picks, baskets, animals, ect. Removing the soil and lining it with stone or bricks to help maintain its shape and prevent erosion or collapses.

Depictions as early as 3200 BC say that King Menes intiated the constrution of a large network of canals and basins in order to harness the niles rivers annual flood waters.

Primary canals (e.g., the Bahr Yussef): diverted water directly from the Nile into major reservoirs or basins

Secondary channels: branched off in order to feed individual basin systems.

Headgates(stone or wooden sluices)— regulated water flow, while mud-brick levees maintained water levels and prevented over-inundation

References:

Bard KA (1999) Encyclopedia of the archaeology of ancient Egypt. Routledge, New York

Dumont HJ (ed) (2009) The Nile: Origin, environments, limnology and human use. Springer.

Egyptian Commission for Irrigation and Drainage (1983) The Nile and the History of Irrigation in Egypt. (M.N. Noaman and D. El Quosy)

El-Sherif M (2012) Agriculture in the ancient Egypt, Faculty of Agriculture, Cairo University

M. Satoh and S Aboulroos(2017), Irrigated Agriculture in Egypt, Springer

Abdelazim M. Negm(2017), The Nile River, Springer.